We know that working in a new way can be a challenge, and the great pivot from face-to-face delivery to live online facilitation caused by the global pandemic is no exception. In our research people reported challenges with engagement in their sessions, facilitator attitude to the modality and actually getting instructors to engage with their audiences.

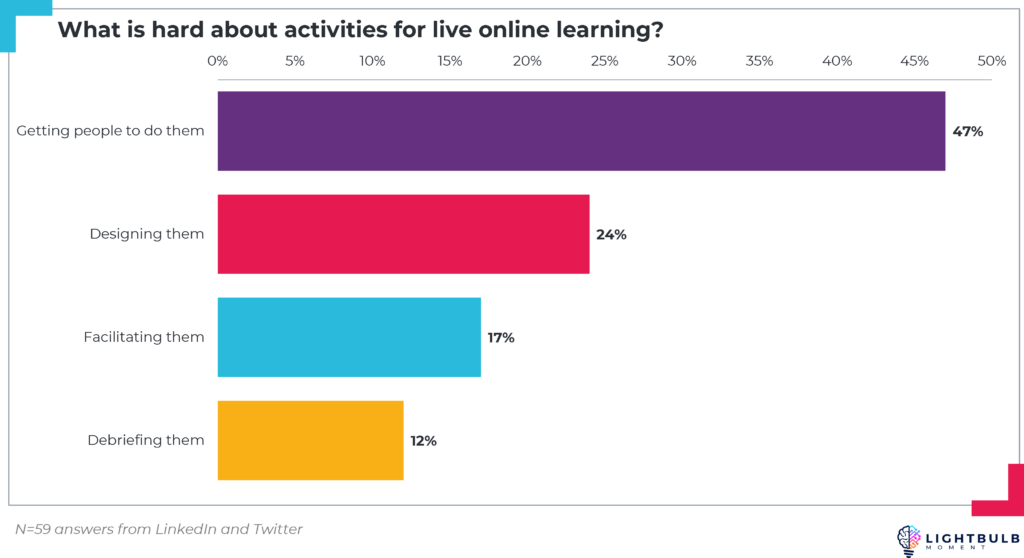

I did some polls on social media, asking just what was difficult with regards activities in virtual facilitation. Overwhelmingly the biggest challenge was encouraging a virtual audience to participate.

We know why we design these activities: they are great for more motivation, emotional involvement, experiential learning, helping people remember and apply everything back at work or in their life. But if we struggle to get people to do the activities, then there are some other changes we might need to make.

Through all of our experience at Lightbulb Moment, we broke down the core points that make virtual learning sessions successful, such as connecting with our attendees as well as focusing on the learning, and put it all back together to create our Human Amplification Model. This model is to help with the design and delivery of virtual sessions to ensure that they are focusing not only on the learner, but on the human aspects of gathering. It’s easy for the technology to be the focus of live online learning, but our Human Amplification Model gets to the core of concentrating on human beings coming together.

Step one: safe

As with all great stories, let’s start at the beginning.

To get our attendees to be participants in our sessions, they need to feel safe to do so. Dr. Amy Edmondson, of Harvard Business School, coined the phrase ‘psychological safety’ and a definition from her is:

“A belief that one will not be punished or humiliated for speaking up with ideas, questions, concerns, or mistakes, and that the team is safe for interpersonal risk-taking.”

This psychological safety applies to every single interaction we have in our sessions. We need to ensure that everyone feels welcome and is given the opportunity to interact in the way that’s right for them and their learning, whilst also respecting other people.

We think that the idea of being able to ask questions and take those risks in a learning environment is absolutely key. We need foster this safety from before the session starts: in the session or course description, the welcome emails and from the moment someone joins the live session. We then bring this through into the introduction, including explaining some basic platform-specific tools we’re using, giving people the option to get involved as much as possible and encourage appropriate interaction for the session being run.

The learning environment needs to be setup by the culture of the organisation, through the sign-up process and includes the training and the follow-up support. There is a lot that the facilitator can do when delivering the session to ensure every person is safe to ask questions, experiment and be open and vulnerable.

For example, I attended a session where the trainer asked a question for people to respond in chat. After about two seconds with nothing in the chat they said, quite sternly “You don’t need to write a novel!“. It was far too quick to be making assumptions that people were writing long answers, participants would barely have had enough time to process the question, move their mouse and click on the chat area, let alone type an answer.

This lack of understanding of how a virtual session works, along with the lack of confidence from a facilitator, can highlight how someone might make people feel too vulnerable to interact, and therefore psychologically unsafe in the learning environment.

Step two: Interactive

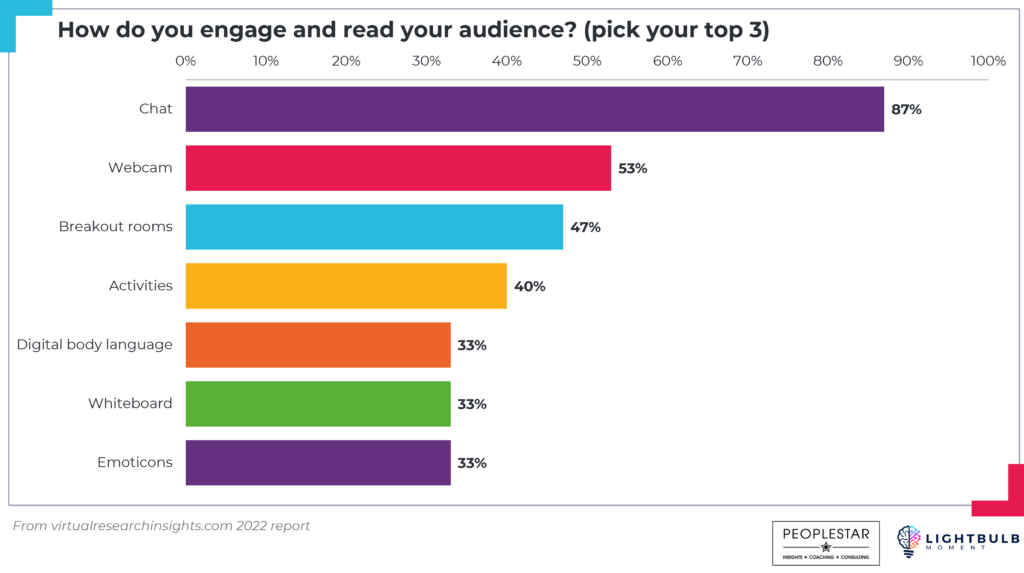

The Human Amplification Model then focuses on interaction in virtual sessions. In our research we asked people how they engaged their audiences, and these were the top options they used:

We love that chat is the top used option, as we find it a really versatile tool and one that’s unique compared to a physical classroom. If there isn’t much or any interaction then facilitators miss out on a lot of opportunities to understand how participants are doing and adapting the session to those needs.

This is about making the most of the time we are live and together. We can get people watching great videos or taking e-learning modules before or after a session, but they can’t ask questions, of us or each other, in the moment. This is the magic of live sessions: the interaction.

All live learning sessions, physical or virtual, need to plan their interactions and not have them as an afterthought. This is especially true of live online learning. The interaction needs to be planned more because it’s different through a virtual platform and that’s a newer way of working for a lot of people. It’s more effortful to design this and it’s hard to do this spontaneously if you don’t know your technology well.

In their article in the International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, Bond and her colleagues wrote that:

“Without careful planning and sound pedagogy, technology can promote disengagement and impede rather than help learning (Howard, Ma, & Yang, 2016; Popenici, 2013).”

The effort put into planning any interaction or learning activity ahead of delivery is important to ensure that it’s meaningful for the learning and the learners. In virtual sessions it’s really easy for the interactions to be simple emoticon responses, like “green tick if you understand”, or polls that are more about making sure people are at the computer than they are about checking learning. Adult learners know the difference between you having a short interaction for the sake of it and really wanting to hear from them!

Link: Psychological safety underpins virtual sessions

Our model shows that each step always links back to being safe:

For example, as a trainer we might have done well at the beginning of the session, as mentioned above, but during a particular interaction it’s possible that we fail on the psychological safety. This could negatively affect one or more participants and impact their future behaviour.

Things that could make participants feel unsafe, or uncomfortable, include:

- Forcing them to interact

- Imposing webcam use

- Directing people to use the microphone

- Too much interaction

- Making people feel stupid, etc.

We need to ensure that people feel comfortable to get involved throughout a session and consistently and meaningfully give participants those opportunities. When we get to the bigger learning activities people are then much more likely to get involved with less effort and stress on them and the facilitator.

Making people feel unsafe is often caused by the facilitator, even if unintentionally, because we are driving the session and often doing a lot of the physical talking (reading out comments/questions from chat, for example). Creating the feeling of not being safe in the session could also be from other people, like a producer, manager who’s attending/observing the session or someone from the learning group itself.

Even if it wasn’t us that created the issue or potential of someone feeling psychologically unsafe, it’s up to us to manage and remedy it.

Step three: Engaged

Interactions are great and we need to get them into our sessions, but it’s possible to have interaction for the sake of it, or at such low level that it doesn’t mean much. The example I used above of “green tick if you understand” shows no learning benefit at all. Other than knowing people are at their device and can click an icon, it doesn’t tell the facilitator much at all. If everyone else in the cohort has put a green tick to say they understand, how likely is it that the last person will say that they don’t?

David Hung and colleagues stated that:

“There is active engagement in the learning process when the learners are constructing knowledge from experience through their interactions with peers and teachers to make meaning”.

Engagement is so much more than just clicking things in the platform. We need to get our participants thinking critically about what they are learning and considering how they will apply it in the workplace. This is where the engagement is fundamental for learning and performance.

In their literature review, Bond and her colleagues collated indicators of student engagement. They focused on engagement in three domains: cognitive, affective (emotional) and behavioural. With cognitive engagement they included that people would be thinking critically, integrating ideas, learning from their peers, reflection and more. The emotional, or affective, elements included enthusiasm, belonging, curiosity, connectedness and so on. The positive behavioural elements included participation, focus, interaction (with peers, teacher, content, technology) developing agency and more. You can download the full list, including disengagement, here.

And where engagement needs to be meaningful, not just green ticks and the odd poll, it needs to be designed into the session from conception. The only way we are going to get really engaged participants is with well planned interaction pieces.

Step four: Connected

How do you know you feel a connection to something or someone? For virtual learning activities it’s about getting really stuck into the conversation or the topic, rather than just clicking a poll option because they have to.

We often get to the end of a virtual classroom and our participants comment that they can’t believe how quickly two hours has passed. In a time where people are getting so much virtual fatigue this feedback highlights to me how important engagement is to connect people with what they are learning and also the people around them.

Having the right session design, session length or number of sessions, and appropriate number of participants in a session will all lead to a facilitator being able to connect with the individuals and the group. This is where the learning for performance impact will have much greater success than sessions focused more on technology or numbers of participants has done in the past.

In Self-Determination Theory Richard Ryan and Edward Deci look at human motivation. Self-determination is about making decisions and taking responsibility for behaviour. One of the elements of their theory is “relatedness”, about connecting with others, being valued, helping our thinking skills by reflecting on the thoughts and experiences of others and more.

Aiming for: digital body language

All of these steps, performed continuously and consistently throughout your session, means you are able to flex to your group and the individual needs.

When most people speak about the difficulties they have with facilitating virtual classrooms, the lack of non-verbal communications, or body language, is high up on the list. When you can’t see individuals or your group it can be really hard to believe there’s anyone at their computers, let alone that they are paying attention and an even further stretch to understand the mood and energy of that group of people.

This is why digital body language is such an important area for facilitators to upskill themselves on. It uses the same concepts that we’re used to but focuses on how those non-verbal communications come across in a virtual platform. When we think someone isn’t sure in a physical session, we might look at their facial expression. Live online we might have their face on a webcam, or it might be their short answers in chat, or lack of any answer at all, that gives that impression.

The reason that interactivity and engagement are building steps towards digital body language, is that without them there’s nothing to observe. In a lecture you might see various faces listening to you. This is very different to when you ask people to work in groups and can observe much bigger differences, such as who is taking over the group, who’s working on their own, who’s trying to calm or cajole someone else and a myriad other observations. Live online it’s through using the platform and external tools and doing activities that we can start to build up our repertoire of similar observations, rather than relying just on the webcam of faces.

It’s from these observations that we can properly flex to the learning needs of the individuals and the groups we are working with. A lecturer in a face-to-face session who doesn’t pay much attention to bored or confused faces might just as well be delivering that live online with no interaction – it’s the same result.

People know good learning

Our participants might not know their Bloom from their Vygotsky, but they don’t need to in order to know when they’ve attended a great learning session, virtual or otherwise. They know if they were motivated to listen and get involved; if their interest was piqued or their curiosity rewarded; if they felt they learned something and can go back to work and achieve what they need to.

Our research highlighted what learners feel made their virtual learning a better experience:

The top responses were the facilitator, the opportunity to interact and a well-designed session, all things that are within our individual control, or that of the organisation when looking at team development of skills and expanding experience.

Summary about human-centred focus in live online learning

By having a safe learning environment, designed and facilitated specific to the needs of virtual learning, the right interaction and engagement activities, and a connection between the participant and their overall learning journey, we can then have sessions that are appropriate to the needs of individuals and the organisation.

This all comes through systematic strategic approaches to not only developing the skills of your L&D team, but also in the culture of your organisation.

And speaking of skills development, we have a free webinar to accompany this blog post and explore the connection element even further.

If you and your team would like to explore developing these skills, have a look at our modularised courses and get in contact to discuss further.